The song I just taught you has some mysterious power.

-Impa

Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time

Zelda’s theme is heard in almost every game of the Legend of Zelda franchise. It is a beautiful example of musical resourcefulness and simplicity. Let’s take a listen to the melody and analyze its sentences:

At a Glance

Before getting to the fun sentence stuff, let’s look at some more broad characteristics of Zelda’s Theme. This track is best described as binary form |A B| on a perpetual loop. If we were to take a look at the chord analysis, it becomes more clear that the binary designation is not totally solid in a classical sense because of the cadences; I’m really only using the term “binary” to denote the piece’s two contrasting sections. Below, I’ll list a quick glance at some of the musical traits of the composition overall:

Zelda’s Theme

- Composer: Koji Kondo

- First use: “Princes Zelda’s Rescue” from The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past (1991)

- Tonality: major

- Texture: homophonic

- Meter: simple triple

- Form: binary |A B| (on loop)

- Melodic Motion: |A| section is largely disjunct, |B| section is more conjunct

- Instrumentation: a prevalence of string family instruments. The harp is especially present in most settings of the melody from game to game, either as the main melodic instrument or the accompaniment

- Notable Features:

- sentence structure drives the phrasing in the |A| and |B| sections

- avoidance of the tonic note and perfect authentic cadences in order to trick our ears into wanting to keep listening as the melody loops

- prevalence of dominant harmonies

The Three Sentences

There are a total of three sentences in Zelda’s Theme. Three sentences…three pieces of the Triforce. A coincidence? Probably.

Anywho:

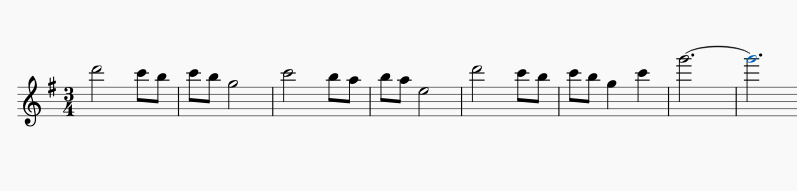

The |A| section is sixteen bars total:

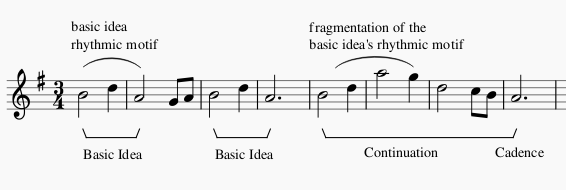

In these sixteen measures, we have two little musical sentences that drive the melody. A typical musical sentence is made of a relatively short basic idea (motif) that is repeated and followed by a longer continuation of that basic idea. Just like a grammatical sentence ends with some kind of punctuation, the musical sentence ends with a cadence. In short, a musical sentence can be described as: [BI-BI-Continuation-Cadence]. Sentences are also quite proportional in that the continuation is generally twice as long as the basic idea.

The first sentence of Zelda’s theme begins with a basic idea presented in the first two measures: B-D-A or mi-sol-re. This melodic motif has an underlying rhythmic structure of alternating note values that will come into play later: half-quarter-half. In measures 3 and 4, we see a repetition of that basic idea. The eighth notes (measure 2, beat 3) could be potentially disruptive to our structure, but I believe that they function more as an embellishment or link (no pun intended) to the next measure. Still, the basic B-D-A motif is preserved in both measures 1 and 2. The continuation takes place in measures 5 through 8 which is proportionally accurate as it is twice as long as the basic idea. Koji Kondo isolates and reuses the rhythmic motif of measure 1 as a template for this continuation, a technique called fragmentation. A half cadence wraps ups this first sentence, aligning the final A note in the melody with a solid dominant seventh chord harmony (V7).

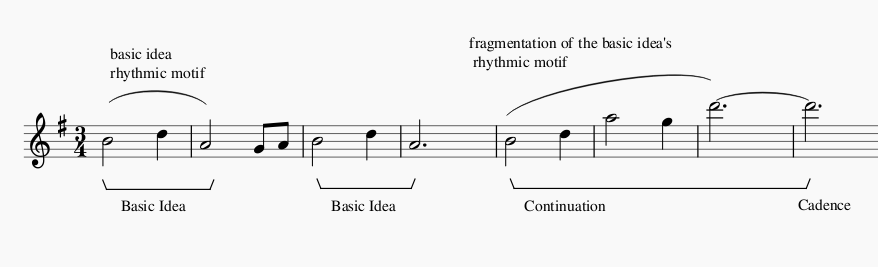

Applying the [BI-BI-Continuation-Cadence] formula to the second half of the |A| section, we can observe the next musical sentence. It is very similar:

The second sentence begins exactly the same way as the first one; they share the same basic ideas, the same rhythmic motif, and the same tonality and underlying harmony. Really, only the last two measures diverge from the first sentence. Here, the melody comes to rest on a high D (sol), emphasizing the dominant harmony in a half cadence.

The |B| section is just eight bars in length:

The eight measures of the |B| section contains the third and final sentence. This time, the sentence structure of the continuation section (the last four bars, see fig. 2) requires a little imagination. You could argue that there is a certain amount of momentum in the continuation which results in launching the melody up to that final, high G. Or, you could also look at the last three notes as a kind of liquidation of the basic idea in the first two bars of figure 2.

Liquidation describes the reduction of a melody or motif to its fundamental components. In the case of this particular sentence, observe the half notes in the first two measures, D–G. They span a downward interval of a fifth. Let’s say that the goal of the basic idea here is to simply move in the direction of a fifth and the eighth-notes in between are embellishment (like the eighth-note embellishment of the first sentence, see fig. 1.2). The last three notes of the continuation, G–C–G, form an inverted fifth plus another fifth, highlighting the fundamental motion of the melody in the first two measures.

Final Thoughts

Koji Kondo is quite resourceful in Zelda’s Theme. Every sentence in every section of the melody relates to one another motivically. The long-short-long rhythmic idea returns again and again. Even the eighth note embellishments are recycled in different ways from sentence to sentence. In terms of melody, Kondo highlights the importance of the interval of the 4th and 5th, which are inversions of each other. This musical resourcefulness and formal simplicity is something that Kondo is a master of utilizing in his compositions overall. I urge you to familiarize yourself with more of his music if you haven’t already!

Simplicity, clarity, resourcefulness, and a bit of creative thinking goes a long way when communicating through music. Musical sentence structure is like the wheel; composers don’t need to reinvent the wheel. Heck, they don’t need to use the wheel at all. But knowing that the wheel is a tool available to them, they can find interesting ways to move things with that wheel.